For years, JaMarcus Crews tried to get a new kidney, but corporate healthcare stood in the way.

He needed dialysis to stay alive. He couldn’t miss a session, not even during a pandemic.

Machine

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Last winter, JaMarcus Crews forced his feet, however numb, to walk a paved public track in the town of Centreville, Alabama, until his calves cramped and sweat bloomed across his T-shirt. He knew the route well, from Library Street to Hospital Drive. He’d walked it as a kid, when he was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes and determined to shed weight. With freckled cheeks and soft eyes, JaMarcus was built big: 6-foot-1, wide shoulders, a round torso on skinny legs. Now, at the age of 36, he was back again. The diabetes had destroyed his kidneys, and he was trying to slim down so that he could get a transplant.

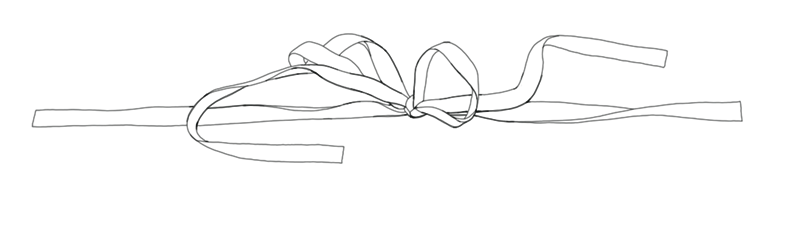

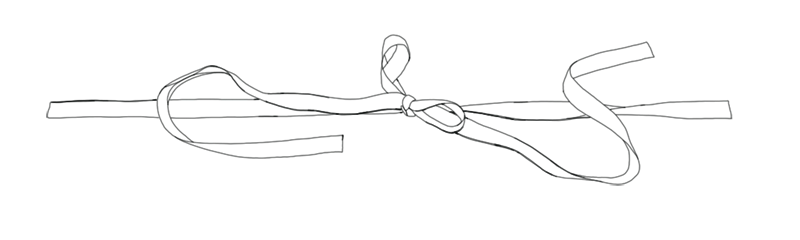

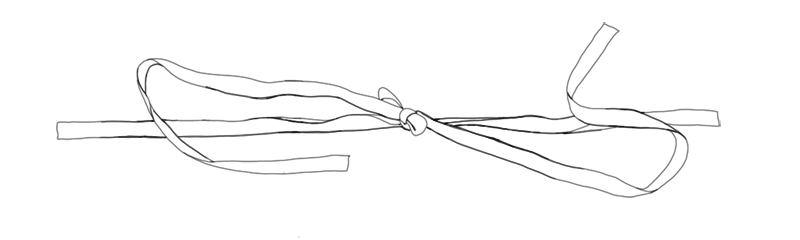

On Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, from 9:30 a.m. to 1:30 in the afternoon, JaMarcus attended a clinic in Tuscaloosa operated by DaVita, one of two for-profit giants in American dialysis. About 20 patients lined the room as clear plastic tubes, coursing with blood, snaked from each person’s arm or neck into a machine. The dialyzers cleaned the waste from their bodies, which their kidneys could no longer do. When it was over, and all anyone wanted was sleep, JaMarcus drove to the wide parking lot at Target to wait for his cashier’s shift. He missed working at the bank, but a nine-to-five was no longer possible.

A stress test had recently suggested that plaque had built up in his blood vessels, giving him coronary artery disease. It was common for patients with kidney failure. If his heart was weakening, he didn’t have much time to get a kidney, but it sometimes felt as if all he did was wait. Of the roughly half a million Americans who depend on dialysis, less than 14% have made it onto a waitlist for a transplant from a deceased donor. JaMarcus had not. He’d been kept off for an array of reasons: spotty insurance, referrals that never came, misdirection about losing weight and what he needed to do to qualify. The first time we spoke, he told me several times: “Dialysis is not for life.” He was convinced that, unless he got a kidney very soon, he was going to die.

JaMarcus searched for diversions. At night, after his wife, Gail, fell asleep, he sneaked out of the house with his teenage son to drive the empty freeways and cruise by the shuttered brick downtown, letting the cold wind hit his skin. In the afternoons, when he shopped for groceries, he drove to the Walmart Supercenter instead of the closer shops, because he enjoyed the bright lights and people-watching, as if it were a mall. JaMarcus didn’t tell his wife or son that he was making calculations in his head: most people didn’t survive five years on dialysis. He was nearing seven. His mother had died in year eight.

No matter how much he tried to go a different way, JaMarcus was being pulled along the same course, one laid out for him at birth. Black Americans are more likely to be born to mothers with diabetes, which predisposes them to the condition. They have lower rates of insurance coverage and can’t see doctors or afford medication as regularly, so diabetes and hypertension are more likely to cause complications like kidney disease. Even clinical care can work against them; doctors estimate kidney function using a controversial formula that inflates the scores of Black patients to make them look healthier, which can delay referrals to specialists or transplant centers.

Although chronic kidney disease affects people of all races at similar rates, Black Americans are three to four times more likely than white Americans to reach kidney failure. Even at the final stages of this disease, they are less likely to get a transplant. It is one of the most glaring examples of the country’s health disparities, one that Tanjala Purnell, a Johns Hopkins epidemiologist and health equity researcher, calls “the perfect storm of everything that went wrong at every single step.”

When patients get to dialysis, they enter a system in which the corporations that stand to profit from keeping them on their machines are also the gatekeepers to getting a transplant. DaVita and Fresenius, its main competitor, control about 70% of the dialysis market. Though most patients rely on staff at these clinics, and the kidney specialists they work with, to educate them about their options and refer them to transplant centers, the federal government’s rules for how they must do so are vague and often toothless. As a result, patients can get direction that’s uneven, depending on how much individual social workers and doctors decide to help. It is a scenario ripe for neglect and the introduction of bias.

JaMarcus hadn’t managed to get on the waitlist when COVID-19 rolled in, first as a distant news story, and then as a threat in the air he was breathing. It was killing Black adults his age at nine times the rate of white ones. People with diabetes made up 40% of the dead; patients on Medicare because of kidney failure were more likely to be hospitalized than anyone else on the government program. It seemed as if the virus was coming straight for JaMarcus, but he wasn’t able to isolate. Every other day, he still needed to trek to a dialysis clinic to spend hours tethered to a machine, surrounded by strangers.

Sometimes, a cough would pierce the quiet. Or an empty chair would prompt rumors that a patient was in the hospital, though no one would confirm whether it was COVID-19. JaMarcus didn’t like to worry Gail. He was more open with his older brother DeArthur, his closest confidant. “I can’t get this shit,” JaMarcus told him. “I really can’t afford to get this.”

JaMarcus was born at 10 pounds, and by 6 months old, he looked to his sister Shirley as if he were doubling in size. Their parents raised seven kids on a single wage; a back injury had left their dad unemployed, and their mom made $3.35 an hour dipping toy parts in paint. Their family had been in Bibb, a rural county halfway between Birmingham and Tuscaloosa, since at least the 1830s, and JaMarcus grew up in a segregated neighborhood, across the train tracks from the town’s white residents. The kids believed that their mom, Mildred, was first diagnosed with diabetes while she was pregnant with JaMarcus.

Their friends and relatives didn’t talk much about the condition, and Mildred didn’t know how it gradually damaged a body, or how diet played a role. They ate greens and beans and sweet potatoes, meat, biscuits, and always syrup. Mildred only saw doctors in emergencies; she didn’t have insurance, and only two local physicians touched Black patients. When her husband was later diagnosed, she joked that she had given it to him, as if it were a cold. You don’t reckon Markie gonna catch it from me too, do you? she would say about JaMarcus. She didn’t know it then, but because she had diabetes, he was more likely to develop it.

Evidence of high diabetes rates among Black Americans had been mounting long before JaMarcus’ birth, but it had largely been ignored. For the first half of the 20th century, diabetes was considered a disease of well-to-do whiteness. And at one point, it was so firmly associated with Jews that it came to be known as the Judenkrankheit, “the Jewish disease,” which was believed to be caused by extreme nervousness, intellectual exertion, or centuries of distress from oppression. After the civil rights movement, when doctors began paying closer attention to the disease in Black neighborhoods, the public was shocked by the high numbers. Years later, in 1985, the government released the first comprehensive report on the health of racial minorities, and it found that Black Americans were 33% more likely to have diabetes than their white neighbors. “People were shocked again,” Arleen Marcia Tuchman, a historian of medicine at Vanderbilt University, told me. But no government funding was set aside to address it.

In her recent book, “Diabetes: A History of Race and Disease,” Tuchman writes that as researchers documented the high rates, what emerged was “a caricature of poor and medically indigent black diabetes patients as lacking intelligence, unable to understand anything but the simplest instructions.” After diabetes was split into two types, people with the autoimmune condition of Type 1, who were predominantly white, were perceived as upstanding citizens who religiously monitored their sugar, Tuchman writes, while those with Type 2 were seen as responsible for their disease. In the past decade, a new wave of social scientists and medical researchers have begun recasting Type 2 as a condition of poverty and discrimination, triggered by factors beyond genes and personal behavior: childhood stress, availability of fresh food, distance from doctors, money. Today, Black adults are nearly twice as likely to develop the condition as white adults. As income levels fall, the rate of diabetes rises. Alabama, JaMarcus’ home state, is among the poorest in the country. It also has the highest rate of diabetes.

JaMarcus’ siblings had commanding personalities, but he was different. “You could hurt his feelings just by looking at him mean,” DeArthur told me. JaMarcus had a stutter, and they mocked him with tongue twisters. They urged him to wrestle and play football at school, but JaMarcus favored housework — cooking and cleaning and washing clothes alongside his mom, in their wooden home across from the Baptist church. By the time he started high school, JaMarcus weighed 405 pounds and was the largest kid in his class. A boy named Jamuel Breeze was the smallest. They figured if they were both being bullied, they might as well link up.

In ninth grade, JaMarcus was playing on the defensive line in a Bibb County High School football game, crouching in his purple jersey and gold helmet, when he collapsed. Unable to stand, he was carried off the field. His coach kept repeating that he was overheated, but when his mother drove him to the emergency room, he was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. “It was shocking to everybody in our circle,” Jamuel told me. “We were all eating the same shit.”

The doctors scared JaMarcus when they talked about his prognosis. One Saturday night, while watching “The Golden Girls,” JaMarcus told Jamuel that he worried he might not survive until prom. He began injecting himself with insulin. He started swapping in celery and apples for junk food, salads slathered in ranch for lunch, flavored water for soda. In the afternoons, he walked the slow roads by Hospital Drive for hours. He lost more than 100 pounds but couldn’t shake his diagnosis.

JaMarcus coped by pushing himself at school. He got on the advanced track for science and math and joined extracurricular groups: Science Club, Key Club, Future Business Leaders of America. He starred in step routines with the Kappa League in the school gymnasium; he was so light on his feet that the crowd would go wild. Almost every day, he approached his only Black teacher, Earnie Cutts, to talk about college or a service project. What can we do for the old folk? he would repeat. Cutts told me: “He was always the spearhead in organizing, and he did it with a meticulousness that many students didn’t have.”

In 2002, JaMarcus moved to Montgomery to attend Auburn University on a scholarship, but he didn’t have insurance or enough cash for his medications. He had aged out of Medicaid at 18. Diabetes is manageable, but without regular healthcare, or money for nutritious food, a slow violence destroys the body. Too much sugar flows through the bloodstream, devastating vessels and attacking nearly every major organ. Nerves die and infections fester; it is the leading cause of blindness and amputations. One of the most debilitating complications is the wreckage of the kidneys, which filter waste from the blood to make urine.

DeArthur, who shared an apartment with him, began noticing that JaMarcus was losing his vision. When JaMarcus met Gail in his hometown in 2003, she joked that she could have found herself a healthier man at the nursing home. He was drawn to her wry sense of humor. By the time they had their son, Marcellus, JaMarcus was 23, and the nerves in his legs were so damaged that he often fell without warning. When he burned his fingertips lighting candles around the house, he felt nothing. Still, he kept up his coursework. In 2006, he got his bachelor’s degree in business administration, with a major in human resources management.

Back home, JaMarcus’ mom had taken a new job driving the dialysis van, ferrying patients to clinics, when she received her own diagnosis of kidney failure. JaMarcus knew that she’d need support; all of his siblings had left for bigger cities, and his dad, who suffered from chronic pain, spent weeks at a time in bed. In 2008, he and Gail decided to move back to Centreville from Montgomery. DeArthur asked him not to; he knew JaMarcus wouldn’t find a good career there. But JaMarcus was adamant: as a kid, he’d promised to care for his parents when they got sick, in the same way they had cared for him. He transferred to a job in Tuscaloosa, as a teller at Compass Bank, with health insurance he could sometimes afford. He didn’t always have the money to pay the premiums. They settled into a three-bedroom apartment across the road from his former high school.

Five years later, JaMarcus’ body began to swell. It started in his feet, then his ankles, all the way up his legs and into his stomach. He was carrying so much liquid that he could hardly walk, as if he was experiencing a flood inside him. Without insurance, he hesitated to see a doctor. In June 2013, he was struggling to breathe when he walked a few steps; it didn’t help to lie down. He took himself to the emergency room at the University of Alabama hospital in Birmingham, and at the age of 30, he was told that his kidneys were about to fail. They were no longer removing excess water from his body. Soon, he would need to start dialysis.

Inequity in kidney care has haunted the field for decades. In 1961, as dialysis machines were entering medicine, the Seattle Artificial Kidney Center established a panel of citizens to decide who should have access to the expensive, life-sustaining treatment. After physicians set medical guidelines, they turned over the decision to the seven members: a housewife, a lawyer, a minister, a surgeon, a state official, a labor leader and a banker. Their task was to determine who was worthy; they based their decisions on patients’ finances, their family size, their education, how often they attended church. Most who made it were white middle-class men. The citizen group was soon dubbed The God Committee. Several years after it was exposed in a Life magazine article, Congress took the landmark step to cover all dialysis patients with Medicare.

At the time, in 1972, only 11,000 people were receiving dialysis, and Congress estimated the number would triple over a decade. But lawmakers didn’t foresee the surge in diabetes — the leading cause of kidney failure — and the numbers began to balloon. “There was this seeming explosion of Black kidney failure that was ‘discovered,’” Richard Mizelle, an associate professor of history at the University of Houston told me, “but the truth of the matter is that many African Americans had long been suffering from chronic and deadly kidney disease.” Today, the United States has one of the highest rates of kidney failure in the world, and about a third of all dialysis patients are Black. Though access to dialysis was radically expanded, the inequity has been pushed to the final, life-saving treatment: transplantation. Donated kidneys are a precious, limited resource, and once again, Black Americans are at a disadvantage.

JaMarcus was an inquisitive patient; when Gail was pregnant, he grilled doctors on their years of experience and read aloud at night about the fetus developing skin and fingernails. For years, he had been asking doctors about his kidneys, concerned that he’d follow in his mother’s footsteps. It wasn’t until he went to the University of Alabama hospital in 2013 that he learned he even had kidney disease. But as he reviewed his old medical records, he looked into his creatinine — a waste product that indicates kidney function — and realized his doctors had seen that it was high. His primary care doctor hadn’t mentioned it. Nor had physicians at the local hospital. “Doctors knew my kidneys were in trouble,” JaMarcus said, “and they didn’t say anything.”

Because he was told so late, JaMarcus’ disease had already advanced, and he wasn’t able to stave off kidney failure. People who don’t see a specialist ahead of kidney failure miss out on drugs that can slow the progression of their disease; they have higher death rates and lower chances of getting a transplant. Black patients are 18% less likely to see a kidney specialist, called a nephrologist, more than a year before starting dialysis. “These race differences in referral for nephrology care have a huge impact on health,” Dr. Ebony Boulware, chief of general internal medicine at Duke University, told me. “The results are about seven times greater mortality.” Insurance coverage is a major driver, but not the only one, raising questions about the role of bias and other barriers in the system.

A race-adjusted equation was also at play in JaMarcus’ case. The formula calculates kidney function by looking at what’s called “estimated glomerular filtration rate,” or eGFR. Creatinine is plugged into the formula along with age, sex and race. Doctors must note whether their patient is “Black” or not. By design, the equation assigns healthier scores to those who are listed as Black, because at a population level, a few studies found that this was more precise. With little investigation into why this might be the case, it was just accepted. That inflated score can mean a longer wait for a kidney because eGFR must drop to a certain level before you can start accumulating time on the transplant waitlist. The best-case scenario is to get a new kidney before needing dialysis, to avoid weathering the side effects of the machines. But those transplants are given on a first-come, first-served basis, and Black patients are less likely to get one.

The researchers and physicians behind the original formula, developed in 1999, wrote that Black patients had higher creatinine levels because “on average, black persons have higher muscle mass than white persons.” The assertion that Black bodies are different from all other bodies keeps company with generations of racist ideas that have infiltrated medicine, some of which were used to rationalize slavery. Researchers who developed the equation acknowledge that race is an imperfect variable, but even though they have updated the formula, they continue to adjust for race. The vast majority of clinical laboratories in the United States use such formulas today.

Over the past several years, medical students have raised alarms about the practice, and recent articles in major medical journals have questioned it. “It doesn’t make any sense,” Dr. Nwamaka Eneanya, a nephrologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told me. “I don’t know why we would think that being Black means that your kidney function is different. I don’t know if you have mixed race in your history. How can I use just the word ‘Black,’ one word, to dictate your care?” A number of hospitals including Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and University of Washington Medicine in Seattle have recently changed their practices. Nephrologists, though, are split. Those who aren’t ready to abolish it argue that removing the variable will carry its own negative consequences — for example, patients can’t get certain medicines like metformin, the cornerstone of Type 2 diabetes management, if their eGFR is too low. Some would prefer to carefully, and slowly, replace the formula with something more precise, like a marker called cystatin c, another indicator of kidney function.

In June 2013, JaMarcus’ race-adjusted eGFR was 25 — too high for the transplant waitlist. He’d need to wait until it was down to 20 before he was eligible. Dr. Vanessa Grubbs, a Black nephrologist who is one of the most vocal opponents of the race correction, had a Black patient in a similar situation. He had an eGFR of 24, which would have been 20 if he were white. Because she didn’t trust the formula, and a cystatin c test wasn’t available, she asked him if he’d be open to trying a more onerous process that most doctors don’t ask for: He would have to collect his urine for a full day and store it in a refrigerator, so she could estimate his GFR with more precision. When she had that sample tested, his GFR was calculated as 20. She referred him for a transplant.

The best treatment for kidney failure is a transplant from a living donor, but JaMarcus couldn’t ask Gail to donate a kidney; she also had diabetes. Most of his siblings did as well. Black patients have far more trouble finding relatives who can donate, because of a higher rate of disqualifying medical conditions. The disparities in living donor transplants have nearly doubled since 1995: Today, white Americans are almost four times more likely to get one.

JaMarcus wasn’t the type to ask strangers for a kidney, either, but he could see that some patients had gone public with their needs. Along the roads in Alabama, bold-colored billboards read: VERNA NEEDS A KIDNEY. MELINDA NEEDS A KIDNEY. JASON NEEDS A KIDNEY. Below the names were photos of each patient — hooked up to a dialysis machine, or hugging their children — with a phone number and a question. “Could you be the miracle I’m praying for?”

In November 2013, JaMarcus started dialysis in Tuscaloosa, a 40-minute drive away, at the same DaVita center that his mom had attended, in a small brick building behind an auto repair shop. JaMarcus’ sister Shirley had asked him to try a different clinic; she hadn’t liked how the staff had treated their mom. But JaMarcus took comfort in the familiar. DaVita was a brand he knew, a Fortune 500 company with more than 2,600 centers, which seemed to be everywhere, across from McDonald’s and Taco Bell.

Dialysis is corporate healthcare on steroids: For-profit companies dominate the market, reap their revenues from Medicare and lobby hard against government reform. DaVita and Fresenius recently spent over $100 million to fight a ballot initiative in California that would have capped their profits, much of which are derived from taxpayer dollars, arguing that the initiative would lead to a shortage of doctors. They have lower staffing ratios and higher death rates than nonprofit facilities. And studies have found that patients at for-profit clinics are less likely to reach the transplant waiting list; they are 17% less likely to get a kidney from a deceased donor. Purnell, the Johns Hopkins epidemiologist, said the whole system is broken as long as corporate dialysis, which is financially incentivized to keep patients, is in charge of steering them to the better treatment of transplant: “Why would I walk into a Nissan dealership to tell me about a BMW?”

Dialysis facilities are responsible for transplant referrals, according to federal regulations, and JaMarcus’ DaVita social worker was assigned to educate and support him. When he was first assessed, a couple of weeks after he began, she wrote that he was suitable for referral and she would get him one when he got insurance. JaMarcus qualified for Medicare within three months. But more than a year later, he still hadn’t been referred.

By 2015, JaMarcus had a new DaVita social worker, Robbin Oswalt, who attributed the delay to a different prerequisite: “He is interested in getting a transplant referral if the Dr. approves after his wgt loss.” JaMarcus had lost 108 pounds since he started dialysis, and his body mass index had been hovering around the University of Alabama’s limit for months. At the time, he didn’t know that his height had been mistakenly entered into his DaVita records as 5-foot-11 — an inch and a half short of his actual height. Their incorrect number was then used to calculate his BMI, which made it look to his doctor that his weight was disqualifying, when it wasn’t.

JaMarcus didn’t like to step on people’s toes. He’d been raised in a family of rule-followers and thought that his social worker would make a referral when he was ready. Unlike many hospitals, the University of Alabama transplant center didn’t allow patients to refer themselves. His social worker needed to coordinate with the nephrologist, Dr. Garfield Ramdeen, who has an independent practice but is also contracted by DaVita as the medical director of the clinic. He rarely came to the center while JaMarcus was there — once a month, twice if JaMarcus was lucky. (DaVita said that someone from the physician’s office made rounds on a regular, often weekly, basis. Dr. Ramdeen did not reply to multiple requests to speak with me.) JaMarcus started to feel as if no one was paying attention. “And that’s what kept me off the list,” he told me.

Dr. Deidra Crews, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins (who is unrelated to JaMarcus), sees patients at Fresenius, DaVita’s main competitor, and says that delays in referral are common. “It’s not a system to move people into transplantation,” she told me. “Reminders would be helpful, protocolizing it so every month social workers are checking in on transplant.” (A Fresenius spokesperson wrote that it has “monthly progress reports” and is “piloting several new technologies’’ to streamline referrals and to better manage patients on the waitlist.) Even DaVita recognized that this was a gap when I asked about it. There are few systemwide rules, and each center has its own practices.

DaVita said that staying on the path to a transplant is a shared responsibility between the doctor, the patient, the transplant center, and the dialysis care team.“We want all patients – regardless of their age, race, health conditions or insurance status – to have access to transplantation, which we believe is the best treatment option for people with kidney failure.” The company wrote that the ultimate decision to pursue a transplant happens between a doctor and a patient. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services note that referrals are a dialysis “facility-level responsibility.”

When JaMarcus’ nephrologist finally referred him to the University of Alabama transplant program, in early 2015, his weight had risen. He explained to Oswalt, his DaVita social worker, that he’d understood from staff at the transplant center that he was a bit too heavy. Oswalt noted this in his chart. She didn’t suggest that he try the center at Vanderbilt University, three hours away, which accepted patients at higher weights. It’s unclear if she even knew it. DaVita did not mandate her to supply that kind of help.

As the routine became more permanent, JaMarcus privately mourned the collapse of his career. At the bank, he’d been hoping for a promotion to loan officer, and recently, he’d been applying for jobs in human resources. But the only work he could find that tolerated his dialysis schedule was a part-time position as a cashier at Dollar Tree. JaMarcus cancelled cable. Instead, he bought bootleg DVDs and the family pretended their home was a theater, microwaving big bowls of popcorn and bragging about it to friends. When Gail’s teenage niece asked to move in, he started parenting her as if she were his daughter. He kept up appearances, still dressing them all in matching clothes: blue sneakers for the men in the family, identical purple button-downs, pink for everyone on special occasions. He committed himself at church, as the treasurer and resident decorator, singing with Gail in the choir.

Low on cash, JaMarcus moved his family from their tidy apartment to his childhood home, with rotting floors, no heat and holes in the windows. He borrowed $50 here and there from family to help cover the gas to get to DaVita, 30 miles away. When he tired of asking, Gail pawned three gold rings, gifts from her father and godmother. “I knew if I didn’t do anything, he wouldn’t be able to get to and from,” Gail told me.

JaMarcus put up a front as he lost control of his body, which was retrofitted to be plugged into the machines. He laughed if blood spontaneously rushed from the port in his neck. When doctors joined a vein and artery in his left forearm, creating a fistula to withstand the needlesticks, he joked about the sight of it, bulging and gnarled. “Feel this! Touch it!” he would say, running his fingers over the blood he felt thrilling beneath his skin. As a young boy, Marcellus mimicked his humor. He knew his father could no longer urinate, and he’d stand over the toilet to tease, “Look dad, I can pee!”

But as dialysis wore on JaMarcus’ body, Marcellus began to worry. At the age of 10, he Googled his dad’s condition. He read about how his father needed dialysis to live, but how it might damage his heart and how he could die. He didn’t want to pry, so he watched most mornings as JaMarcus vomited up the fluid that his body could no longer handle. In silence, they’d get in the car and drive to school.

When JaMarcus began seeing a nutritionist, in 2019, he said that he wanted a transplant because of Marcellus, whom he called his “mini-me.” His son was approaching the same age he was when he was first diagnosed with diabetes. JaMarcus told the nutritionist that he worried Marcellus was “headed down the same road.” Each month, JaMarcus used his glucometer to check his son’s sugar levels. He taught Marcellus to watch his weight and brought him along to walk the track.

JaMarcus no longer needed a doctor’s endorsement to get a referral for a transplant; a year earlier, DaVita had changed its rules to allow patients to ask for a referral when they wanted one, regardless of whether their physician thought they were a good candidate. The company made the decision in order to remove the influence of implicit bias. JaMarcus had been waiting until he could bring his BMI of 36 down to 35, which is what he’d been told he needed to hit in order to qualify. But the University of Alabama transplant program had raised its body mass index limit to 40 back in 2015. The hospital didn’t publicize its new standards on its website, and no one at DaVita had told him. For years, he’d been eligible.

When I mentioned my confusion about this to DaVita, a spokesperson replied that their social workers aren’t transplant coordinators but transplant advocates. When I asked why they didn’t provide basic facts on the requirements at nearby hospitals, DaVita replied in an email that the responsibility to update patients on criteria falls to transplant centers. Years ago, DaVita tried to argue against federal regulations that require dialysis care teams to assess patients based on the criteria at the prospective transplant center, claiming that this was “beyond the reasonable scope of practice” for most of its staff. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, though, explains in its guidelines that “if the dialysis facility refers patients to multiple transplant centers, the dialysis facility should have the selection criteria for each center on file and available to patients.”

Over time, the setbacks eroded JaMarcus’ optimism. He’d tried pursuing a master’s in education through the University of Phoenix, but he couldn’t afford the tuition. He would watch what he ate and take long walks, only to fall behind on his medication and binge on sleeves of fun-size chocolate bars. Sometimes, he’d call DeArthur just to vent: I don’t understand. What did I do? What did I not do? JaMarcus had always been slow to anger, but DeArthur noticed he was developing a temper. Occasionally, he cussed DeArthur out, hung up, and called back to apologize.

This March, JaMarcus got the news he’d long been waiting for: he was being referred to the University of Alabama transplant center. Under normal circumstances, staff at the center would have contacted him within two days. He would have had an appointment at the clinic in Birmingham within a month, and spent the following weeks getting tests with his doctors: an echocardiogram, a stress test, a CT scan. He expected that he would then be approved for the waitlist. If he could get on it, his time would be backdated to when he started dialysis in 2013, and he’d be near the top of the list. Chances were good that he could get a transplant within a year.

Like everyone this spring, his plans were interrupted by the coronavirus. First, Marcellus’ middle school shut down in the middle of March. JaMarcus and Gail drove to Sam’s Club to stock up on toilet paper and sanitizer and water. Then, Gov. Kay Ivey issued a statement on the state’s first confirmed case. “Alabamians should not be fearful,” she said. “Alabamians are smart and savvy, and I know they will continue taking appropriate precautions.” Two weeks later, word started to get around about the first person in town who’d contracted the virus. At 58 years old, he’d been placed on life support.

JaMarcus recognized that his immune system, weakened by diabetes and kidney disease, was no good at protecting him. So he took a leave from his new job, on the check-out line at Target, retiring his red shirt. Since Gail couldn’t drive, JaMarcus masked up to buy groceries. Each time he arrived back home, he left the plastic bags on the porch, threw his clothes in the washer and soaped himself down in the shower. Gail trailed him through the house with Microban, spraying the knobs and light switches.

Every once in a while, strange symptoms set in, and he wondered if the virus had caught him. In April, just before his 37th birthday, his ears started ringing and aching, and he ran a low fever. The local hospital denied him a COVID-19 test but told him to self-quarantine. He moved into Marcellus’ bedroom, where his son would leave him ramen at the door. When he called his dialysis clinic, staff said to come in to his normal shift with a mask, like everyone else. (DaVita told me that, for the most part, they treat patients with suspected COVID-19 in different facilities or on different shifts from the general population.) In May, the earache came back stronger, this time with a cough. He got a COVID-19 test and it came back negative.

That month, JaMarcus decided to put his goal of a transplant before his worries about the coronavirus. He switched from morning dialysis to night sessions, because he wanted a full-time day job with insurance. Anyone on Medicare because of kidney failure loses that coverage three years after a transplant, so patients need private insurance for the lifelong medicines that follow the surgery. (The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill last week to cover these immunosuppressive drugs; the Senate is expected to vote on it soon.) Night dialysis meant attending a new clinic, which held seven-hour sessions in the evenings. Gail hated the routine and its risks, but she slowly acclimated. When JaMarcus got home around 2 a.m., before he lay down to sleep, he would reach by their wrought-iron bedpost and gently squeeze her toes.

On a warm night a few weeks into JaMarcus’ new regimen, a man known as Big Eric started shivering in his chair. While JaMarcus and the others remained hooked to their machines, an ambulance arrived and rushed Eric to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19. JaMarcus knew several people in town who’d been admitted with the virus and had made it out alive. Then he learned that Eric was dead.

Black Americans were dying of COVID-19 at nearly three times the rate of white Americans. For anyone familiar with the disparities that have long plagued health care, this was not surprising. But once again, headlines heralded the “shocking” and “alarming” figures. Jobs, housing and testing all played their parts, but it was impossible to ignore how conditions like kidney failure, and its leading causes of diabetes and hypertension, were already distributed across the country, making certain Americans particularly vulnerable. Far too many of these patients had already been left behind by a health system never set up to care for them.

Despite all of the research on racial disparities in transplants, the government has been slow to implement reforms. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requires dialysis centers to “inform” their patients about transplant options, but it hasn’t standardized exactly what they need to communicate. One study out of Georgia found that the transplant referral rates in the first year of dialysis ranged from 0% to 75% among clinics, and the variability could not be attributed to measured differences among patients. The government hasn’t tracked or publicized referral rates at different centers, or set up penalties for those on the low end.

Last year, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to improve kidney care, in which he proposed changing Medicare payments to incentivize more transplants. The order did not include measures to ensure that patients were equitably referred, evaluated and waitlisted for transplant. Many kidney researchers were left wondering when the federal government would prioritize equal access. This summer, physicians and advocates took one step to address fairness in clinical formulas. The National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology formed a task force to assess the race-correction equations. They wrote that “race is a social, not a biological construct,” and that they “are committed to ensuring that racial bias does not affect the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of kidney diseases.” They expect to announce an update later this month.

When I spoke with JaMarcus in early June, I could hear the frustration in his voice. “If I were on the donor list, I would have received a kidney by now,” he told me. He was livid that the process had been this difficult to navigate, and he was worried about his friends in dialysis, many of whom didn’t have a high school education. He had a degree in business — he had nearly completed a Master’s, he repeated — and still, it seemed as if his doctors, his social worker, his clinic, the entire system, was working against him.

It wasn’t until July that things started looking up. In his night clinic, JaMarcus had a new social worker, Candice Morrow, who was helping him apply for financial aid to cover gas money, and his care team was following up on his referral. Morrow left him handwritten notes about her progress. “Just didn’t want you to think I forgot about you,” she signed off. The surgical director of the kidney transplant program at the University of Alabama told me that the first record they have of a referral this year was not in March, but on July 9. “Not all good candidates get to the transplant center,” Dr. Michael Hanaway said. “This is an inefficient system that does not serve patients well. Many, many patients get left behind.”

To Hanaway, JaMarcus looked like a good candidate: young, otherwise healthy, with a fine BMI. He had made it down to 258 pounds that summer, earning him the nickname Slim Shady. It seemed like everything he had done over the past several years had primed him to get on the list. After he got an angiogram, he even learned that he didn’t have coronary artery disease. “I got a heart like a teenager!” he gloated to Gail, when he got home from the cardiologist. “Baby, I can do it all.”

When his ears began ringing again in July, JaMarcus didn’t think much of it. There was a whistle in his breath, and he’d lost his appetite, but it seemed like a simple cold. On July 14, he called in sick to dialysis. But two days later, when he stood up to drive to his next session, it felt to him as if the room was spinning. When he made it to the front door, he announced that everything looked blurry. Confused, Gail called DeArthur, who drove up from Montgomery and took his brother to the hospital.

With too little oxygen in his blood, JaMarcus was admitted to the intensive care unit at DCH Regional Medical Center, where he lay facing a shaded window and a wall-mounted clock. He alternated between an oxygen tube and a BiPAP, a kind of air mask, to breathe. After his lab work and chest X-ray came back, he was diagnosed with sepsis, respiratory failure and pneumonia. Then his test came back positive for COVID-19.

When his relatives texted him, JaMarcus shot back casually. “Thanks for checking on me,” he wrote to his nephew, “I’m doing fine just got to get better tho.” Marcellus texted: “Mommy don’t want to talk…. are u ok… u want to call me and talk or what.” JaMarcus replied: “Doing well son.” His younger brother teased, “How ya feeling boi? You gotta give me at least 10 to 15 more years before you can kick tha bucket…” JaMarcus wrote: “I’m trying not too.”

Gail spoke with him every night, until 1 or 2 in the morning. She sang gospel songs in her strong alto, and she prayed aloud. JaMarcus had always thought that her prayers reached God quicker than his. And he didn’t want to let his body drift from consciousness. “He would never want to hang up,” Gail told me. “He just wanted me to be on the phone.”

On July 29, the doctors started talking about putting JaMarcus on a ventilator. Gail asked him, “Is there anybody else that you want to talk to before they put you on the machine?”

JaMarcus said: “I’m talking to her now.”

Gail didn’t dare say it, but she couldn’t stop thinking about a text she’d received from him earlier. All he had written was: “I’m so scared.”

On Aug. 8, dozens of young families in masks gathered in the yard of Present Truth Church, facing a powder blue casket with silver hasps. There, JaMarcus lay with his arms by his sides, in a white suit and baby blue tie. Under a hot sun, several women in face shields and gloves sang worship songs as Marcellus fanned his mother with a funeral program. After the poetry and the prayers, a caravan of cars drove past JaMarcus’ childhood home, his elementary school, the church where he was married, to a cemetery, tucked into a forest, where his parents were buried.

JaMarcus died on July 31 at 7:29 a.m. The hospital had allowed Marcellus and Gail to say goodbye, and in the fluorescent light, they had stood beside his bed. Marcellus wrapped his hand around his father’s finger, which was warm. JaMarcus coded once, then twice, and he was gone.

At first, Marcellus didn’t know how to feel. He told me that it was like genjutsu, a concept he’d learned from a Japanese anime series, in which a victim’s senses have been disrupted, and he moves through an illusion of a world that is not real. Hours after JaMarcus died, Marcellus texted his dad: “Wassup.” When he realized that his father wasn’t coming back, he wrote to him for guidance: “If u can some way can u replied back to me to see are u ok please dad.”

In the weeks after, Gail rarely moved from her bed. She cried, she played Wheel of Fortune on her phone, she put herself to sleep with melatonin. She punished herself daily by scrolling to a photo she’d taken of JaMarcus in his coffin. Sometimes, Gail got angry about all he had been through at dialysis. At other times, she was grateful that he didn’t have to suffer it any longer.

When I brought details of JaMarcus’ care to DaVita, they told me that there was no record of him or his family filing a complaint or sharing negative feedback. “The transplant system is complex, and it’s difficult to hear about experiences like JaMarcus’, who didn’t make it onto the transplant center’s waitlist even after his physician referred him several times. JaMarcus was a beloved patient we supported for many years. Our hearts are with his loved ones, and our care team is grieving his loss. Alongside the entire kidney care community, we will continue to advocate for transplant and actively push for progress to the system.”

I visited Gail and Marcellus in September, and most days, we sat in their dark living room. Gail curled into her favorite recliner, surrounded by reminders. Fake white roses that JaMarcus had coiled into a bouquet. Framed photos of Gail, with the note, You’re still the one. She hadn’t let Marcellus return to school, and she was still scared to go outside.

One Friday night, Gail was trying to get some clarity on all the bills, which kept arriving in her mailbox. JaMarcus, like all dialysis patients, didn’t qualify for a traditional life insurance policy, and Gail didn’t have a job. She was sorting through the mail as we talked. Amid the junk sat a University of Alabama Medicine envelope. She picked it up and read it silently: “The UAB Transplant office has received a referral for transplant evaluation from your local nephrologist,” it began. The transplant center was writing to schedule an appointment.

Gail leaned her cheek on the headrest. “Lord have mercy,” she said. Tears dripped out of the corners of her eyes. She let her mind imagine JaMarcus celebrating: “Gail, Gail! Can you believe it?” She pictured him shouting. “I’m getting a transplant.”